Cumbres & Toltec

Cumbres & Toltec Instead of renting our usual tour bus for $1000, Continuing Education borrowed two small van s from the University of New Mexico so that they could affordably transport 22 people to our latest adventure on the 125-year-old Cumbres and Toltec Scenic Railroad.

s from the University of New Mexico so that they could affordably transport 22 people to our latest adventure on the 125-year-old Cumbres and Toltec Scenic Railroad.

Lorenzo was the driver of the van I was seated in and that meant I had to listen to him play his harmonica and sing along with the rest of the group. I’m really not much for all this cornball stuff but I must say that his rendition of “You Are My Sunshine” was very good.

The vans were cramped but we had much cleaner windows than our usual decrepit bus and the seats were solid and the ride smooth. The vans got great mileage and we got to our destination in a fraction of the time.

The vans also lent to a much more sociable and less isolating experience than a bus since we were all piled in them like sardines. About the only problem I faced was the strong odor of perfume that some of the ladies were wearing, so I insisted that we turn up the ventilation . . . Way up.

Built in the late 1800’s, the Cumbres and Toltec narrow gauge railroad is known throughout the world as one of the best preserved railroad museums and is the finest example of narrow gauge, mountain steam railroading in the country. It was originally used to haul minerals, cattle, sheep and timber. The train also carried a parlor car on its daily run until that service ended in 1951.

In 1970 New Mexico and Colorado bought up the most scenic portion of the railroad, from Chama to Antonito. The railroad is run through a bi-state commission, contracting for services with two non-profit corporations. It has been designated as a National and State Registered Historic Site and National Civil Engineering Landmark.

Historic Site and National Civil Engineering Landmark.

As an obsessed rail fan (or “foamer” as we are sometimes known), I was excited to be part of this adventure and thrilled that I didn’t have to drive up to Chama and deal with all the logistics involved in arranging this two day trip.

The drive from Albuquerque to Santa Fe was pleasant. As we were leaving the Duke City I noticed with sadness large cranes hovering over the old Beach Water Park, dismantling its majestic, sweeping slides and towers. I once attended a Leon Russell concert there and listened to him sing as I paddled around the crystal clear waters of its undulating wave pool under a starlit sky. And I have boldly slid down those slippery slides more times than I can remember.

sing as I paddled around the crystal clear waters of its undulating wave pool under a starlit sky. And I have boldly slid down those slippery slides more times than I can remember.

We avoided The City Different by using state road 599, also known as the Santa Fe bypass, originally built to transport trucks carrying low-level nuclear waste to the Waste Isolation Pilot Project in Carlsbad. I was amazed to see expensive homes popping up along its roadside.

Our guide for this excursion was Jill Lane, owner of the Elkhorn Lodge in Chama, New Mexico.

Well, now that you have a little background information, I’m going to kick back and let you read the journal that I kept during my  adventure on the Cumbres and Toltec Railroad.

adventure on the Cumbres and Toltec Railroad.

The road to Chama is windy and scenic, passing many small villages and abandoned gas stations. Road signs direct you to the Sanctuario de Chimayo, one of the most sacred Churches in the world. Built in 1816 by Bernardo Abeyta to honor Nuestro Senor de Equipulas, it is famous for its tradition of healing the sick. Every Easter, believers from all over the world make pilgrimages to the Santuario.

I smacked my skull on the adobe doorframe leading up to the room with the hole in the floor, the one that contains sacred dirt that supposedly never gets empty, no matter how many scoops are removed from it.

No flash photography is allowed inside of the Church but I got some nice exterior shots of the Church and was especially enchanted wi th the luxurious accommodations given to pigeons.

th the luxurious accommodations given to pigeons.

Next stop was Ghost Ranch in Abiquiu where we toured the visitor’s center, admired the colorful beefsteak mountains made famous by Georgia O’Keefe and had the rare privilege of watching a hairy tarantula cross our path.

Then it was off to Tierra Wools in Los Ojos where we got an education in hand woven tapestry made from descendants of sheep brought over by the Conquistadors. Although I was not able to afford a $600 rug, I did find a nice little woven coaster for my sister’s birthday.

And then we headed to Chama and the Elkhorn Lodge where my septuagenarian roommate Mathew and I checked into our room in a real log ca bin.

bin.

After settling down, we took a little side trip to beautiful downtown Chama. There we checked out all manner of railroad-inspired chatchkeys and then crossed the main street to admire a steam locomotives that had just pulled into the station.

Since I was wearing my Canadian National Engineers cap we were invited to inspect the locomotive close-up and even allowed to step into the cab, so long as we promised to touch nothing. I swear: that filthy old railroad cap has opened more doors to me among rail fans and Amtrak employees than I can count.

Our group ate well that evening at a local diner. Mathew and I, who have bonded quite nicely, split a large pitcher of Fat Tire beer which he gen erously paid for. For dinner we both ordered a satisfying offering of chicken fried steak with gravy and pan fried potatoes.

erously paid for. For dinner we both ordered a satisfying offering of chicken fried steak with gravy and pan fried potatoes.

The waitress was totally overwhelmed by our group and the fact that we all wanted separate tickets. She was curt to us, but a few members of our group were curt to her in return. So I gave her a 30% tip to help make up for the stinginess and impatience of my companions and to reward her entertaining ways.

After we got back to the lodge I sank into the 104-degree waters of their brand new Jacuzzi. I had the hot tub all to myself and I worked out many aches and pains.

Now I’m seated in the coach car on the Cumbres & Toltec Railroad! This car has 11 rows of seats, separated by an aisle and can accommodate 44  people. The seats are made of soft, supple leather with wooden armrests. A long metal bar lies conveniently at foot level and the backs of the seats can be flipped around when the train reaches the end of the line and reverses direction (or when people want to chat with those seated in front of them.)

people. The seats are made of soft, supple leather with wooden armrests. A long metal bar lies conveniently at foot level and the backs of the seats can be flipped around when the train reaches the end of the line and reverses direction (or when people want to chat with those seated in front of them.)

The sides of our unheated coach is lined with plenty of windows that open from the top and slide down into a recessed area located between the outside of the train and the varnished wood of the inside wall. The cars have intricately crafted wood doors and the vestibule floor (the space connecting two cars) has a floor made of corrugated metal, surrounded by a cast iron railing that must be negotiated with great care lest you fall out.

The train will be pulled up the steep Cumbres Pass by two locomotives that will pull 10 cars at a top speed of about 20 mph. This may not seem very fast, but the train was state-of-the-art for its time and  with scenery as glorious as that found in Northern New Mexico and Southern California, it is a mystery why anybody would want to go any faster!

with scenery as glorious as that found in Northern New Mexico and Southern California, it is a mystery why anybody would want to go any faster!

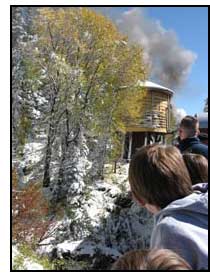

It’s a picture perfect day. Only a few tiny clouds in the sky and the weather is so warm that I am starting to remove the layers of clothes that are mummifying my body. It snowed the day before, reaching a depth of 10 inches. The snow was so deep, and so blinding that the train was not able to complete its trip and vouchers had to be issued to the disappointed riders.

The town of Chama is located at 7,850 feet and we will eventually be heading up to 10,000 feet. One of our three docents has just explained safety regulations before we start.

A long, high pitched whistle announces our departure from Chama. Our train is being pulled by two steam locomotives that belch white and black smoke and slowly lumber over tracks that go clickity-clack over its narrow, three foot wide rails. Swaying from side to  side we pass fields with wildflowers and in the distance are snow capped mountains.

side we pass fields with wildflowers and in the distance are snow capped mountains.

I leave the coach compartment and head into the open air gondola car. People line the roadways and the fields snapping pictures and scores of people wave to us from the roadside. The docent instructs us to wave back to them and choreographs our movements in perfect unison, from left to right to center and back again.

“Spectacular! Picture perfect! We couldn’t have picked a better day!” is what people all around me are saying as we slowly meander almost 3,000 feet up toward Cumbres and the highest point on the railroad.

The scenery is so spectacular that it becomes almost overwhelming at a certain point. I snap pictures at almost every bend but there comes a time when I just want to take it all in. Every Kodak moment is better than the last as we leave the 20th Century behind us and enter pristine wilderness while the sun beats heavily against my face.

The landscape becomes covered in a foot of snow as nature reveals itself to me. I am packed tightly amongst friendly, smiling, beautiful people in this open air gondola car, breathing fr esh clean air. We climb into the sky, higher and higher, further back into time, beyond the roads, past crumbled telegraph poles, their ancient wires broken, past the ruins of sun bleached snow fences that once held back 30 foot snow drifts for a train that used to run every single day, even in the harsh winter months.

esh clean air. We climb into the sky, higher and higher, further back into time, beyond the roads, past crumbled telegraph poles, their ancient wires broken, past the ruins of sun bleached snow fences that once held back 30 foot snow drifts for a train that used to run every single day, even in the harsh winter months.

The Cumbres & Toltec does not run in the winter anymore. The snow drifts get so high in the winter that trains used to get buried in it. But that was OK because they had the fires of the furnace to keep them warm and tons of coal to feed it until they were rescued by another locomotive that had an enormous fan in front of it to blow the freshly fallen snow out of its path!

It just doesn’t get any better than this for an old foamer like me. You would never be able to become so intimately in touch with the earth and the land and the sky riding at 90 mph aboard Amtrak. There, the vestibules, (that space between the cars) is shielded from the outside by flexible walls that insulate you from the outdoors. The windows on Amtrak don’t open and the air is re-circulated.

But here, aboard the Cumbres & Toltec Railroad, the windows on the coaches can be opened up to two feet wide and if that isn’t enough to satisfy your craving for fresh air, you can walk to the gondola car  and be separated from nature by only a four foot wooden railing. Or you can always find some privacy in that precious space between cars, where you can lean back against a car in the open air and reflect upon the glory of nature as the rails beneath you go clickity-clack, clickity clack.

and be separated from nature by only a four foot wooden railing. Or you can always find some privacy in that precious space between cars, where you can lean back against a car in the open air and reflect upon the glory of nature as the rails beneath you go clickity-clack, clickity clack.

If this antique railroad was not here as a priceless legacy of the past, it could not be built today: Environmental and legal concerns (the railroad passes between New Mexico and Colorado 11 times) would make such a railroad impossible to be built. But it’s here and it’s now and if you ever have the opportunity to ride it, seize upon that lucky moment because it is better than anything I or any travel brochure could ever say.

Upon our arrival at Osier, the half way point, all four hundred of us step off the train and enjoy a generous, all-you-can eat lunch of turkey and all the fixings. If that bill of fare doesn’t suit your fancy, you can eat a salad lunch or even meatloaf. The price of the generous lunch is included in the cost of the ticket.

The second half of our journey, from Osier to Antonito is proving to be equally spectacular as the first half, but much different. Here, the scenery is dominated with giant gorges and lush stands of aspen, birch and ponderosa pine. We pass through two tunnels, one carved into solid rock walls and the other dug into the ever-shifting mud.

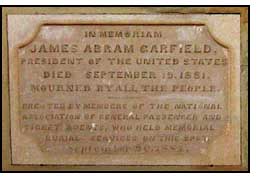

We pass a large stone memorial that was built in the memory of President James A. Garfield after his assassination in 1881 and we must take care to avoid large branches that lash out at our faces in the open air gondola. At one point the train comes to a halt so that the engineer and brakeman can remove a big rock from the track.

We pass a large stone memorial that was built in the memory of President James A. Garfield after his assassination in 1881 and we must take care to avoid large branches that lash out at our faces in the open air gondola. At one point the train comes to a halt so that the engineer and brakeman can remove a big rock from the track.

The ever-belching smoke stacks of the steam locomotives baptize us with low-sulfur ash, soot and coal dust. It gets embedded into our eyeballs and covers our faces. These locomotives never rest. Even at night their fires are kept burning because of the difficulty of starting them up again in the morning. From spring until fall the fires in these locomotives burn: Burn like the fires of Hell.

It takes three tons of coal to get the train from Chama to the highest point of the route and two tons to get it the rest of the way to Antonito. The train can hold eight tons of coal and this coal is trucked in locally from mines in Colorado.

Passengers are lulled to sleep by the rocking movement of the train and the after-effects of our delicious turkey dinner. The scenery becomes more rolling and pastoral as we near the end of our trip. The snow is all gone now as the weather warms and we, once again, approach lower elevations.

The skies are so clear that we can see Great Sand Dunes National Monument in the distance. Cows graze on the surrounding land and water themselves in a small brown pool, startled by the train’s whistle that blows at every corner; they chase us for a spell and then go about their business. A sharp eye can see long horned antelope and elk in the distance. The air gets cooler as the sun begins to sink in the horizon.

The final leg of the trip to Antonito has its own distinction but is not nearly as spectacular as the first half. The land is rolling and the gorges, mountains and  trees are long gone.

trees are long gone.

Our docent, Bob Ross, keeps our interest by telling us stories about places along the track with names like Tanglefoot Curve, Whiplash Curve and Lava Loop . . . Behind every twist and turn of the tracks there is a story.

Like Hangman’s Trestle, also known as Willie Nelson’s Trestle. Back in the old days a man named Ferguson managed to really piss off some people in Antonito. So one day they stole an engine from the train yards and transported Ferguson to the trestle, where they hung him from the neck until he was dead.

Bob also tells the story of how Willie Nelson made a movie in 1988 called “Where The Hell’s That Gold?” starring himself and Delta Burke. In the course of filming a staged explosion, the trestle was accidentally burned down. Willie had to rebuild the trestle, thus securing an alternate name for the structure.

No sooner has the our train ride ended then we are transported, back to the future on a modern coach which will take us back to Chama, our vans and to Albuquerque. The bus returns us to Chama in only one hour, after a train trip that covered that same distance in eight.

It’s been a lovely day and I am glowing. The many advantages of traveling with Continuing Education’s “Story of New Mexico” program become clearer to me with every field trip that I take. Not only did traveling with my newfound friends in Continuing Ed make good money sense, but it was also a lot of fun!

Thank you for visiting Chucksville.

|

|

|

|