Billy The Kid

Billy The KidBy Charles Reuben

shawnee@unm.edu

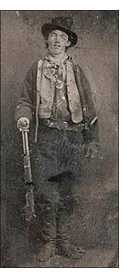

Billy The Kid, Kid Antrim and El Chivato were the nicknames given to William H. Bonney during his short life. He weighed 125 pounds and was five feet,  three inches tall during his prime. Born in New York, his Mother and brother Joe migrated to Santa Fe and then Silver City, NM after Billy’s Father died. Billy’s Mother died a year later and after living with relatives and in foster homes, he decided to live on his own when he was about 14 years old.

three inches tall during his prime. Born in New York, his Mother and brother Joe migrated to Santa Fe and then Silver City, NM after Billy’s Father died. Billy’s Mother died a year later and after living with relatives and in foster homes, he decided to live on his own when he was about 14 years old.

An attractive young man who loved to dance and was popular with the ladies, Billy found it was easier making a living stealing horses than working a day job. Eventually he joined up with a gang and found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time. Accused of killing people he did not kill, Billy was sent to jail but appealed for clemency from the Governor who ignored his repeated requests for a pardon.

Billy finally got fed up, escaped from jail again and met his maker in a shoot out at the Maxwell Estate, located right next to old Fort Sumner. In the end, his death was ascribed to be part of the Lincoln County War. And although over 200 men were said to be involved in that bloody conflict which pitted established businesses against new enterprise, only Billy the Kid was accused of doing anything wrong and had to pay the ultimate price.

My recent foray into Lin coln county and Billy the Kid was part of a field trip that I recently took as part of the University of New Mexico’s Continuing Education program to explore New Mexico.

coln county and Billy the Kid was part of a field trip that I recently took as part of the University of New Mexico’s Continuing Education program to explore New Mexico.

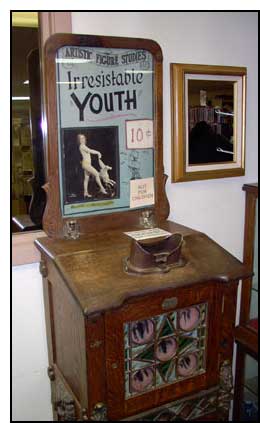

When we reached the sleepy town of Fort Sumner, we stopped at the Billy The Kid Museum. A sprawling building filled with 60,000 relics artifacts and a gift store complete with Billy he Kid memorabilia, souvenirs and an R-rated stereopticon that will, for the price of a dime, give you a three-dimensional slide show of a naked young woman riding a hobby horse. You can spend the whole day there looking at old typewriters, old cars, and old washing machines. If it’s old and tired, you will probably find it at the Billy the Kid Museum and the meager price of admission ($4 adults, $2 children, $3.50 seniors) makes the experience all the more inviting.

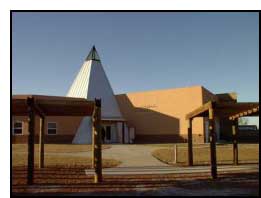

The focus of this field trip was actually not Billy the Kid. Our main purpose was to visit the Memorial at Bosque Redondo, which is a  brand new museum opened last June, commemorating the “Long Walk” taken by the Navajo and Mescalero Apache Indians in 1868.

brand new museum opened last June, commemorating the “Long Walk” taken by the Navajo and Mescalero Apache Indians in 1868.

But first a little history lesson. In 1863 the US Army forced 15,000 Navajo and Apache Indians to leave their homes and assemble in a vast reservation in eastern New Mexico called Bosque Redondo. The water was alkaline and the crops would not grow in their new home and their sheep, a source of wool and nourishment plummeted from a hundred thousand head to a mere thousand or so.

Twenty percent of the Indian population died during their forced relocation and those pregnant or sick people who held up the march to Fort Sumner, the home of Bosque Redondo were shot. Upon arriving in their grim new home, the Indians tried hard to make things work out but the land would not bear fruit, the water was foul and the the rations that the Army gave to them were meager.

The rations, food unfamiliar to the Indians, caused them to get sick and were g radually decreased from two pounds per person per day to only half that. At this point, the Apaches got so disgusted that one night they just all decided to get up and escape. They left in many directions, making it difficult for the Army to recapture them. The Navajo stayed put, however.

radually decreased from two pounds per person per day to only half that. At this point, the Apaches got so disgusted that one night they just all decided to get up and escape. They left in many directions, making it difficult for the Army to recapture them. The Navajo stayed put, however.

After living in that hell hole for five years, the Bosque Redondo reservation started to get the attention of politicians in Washington D.C. because of its exorbitant maintenance costs, its dismal failure at becoming self-sufficient and reports of starvation and genocide that were circulating.

Congress sent a delegation to the area to try to convince the Navajo to move to “Indian Country” but the Navajo refused saying they’d rather stay at Bosque Redondo than move to Oklahoma. The Navajo eventually got their own way and a vast reservation was established in the four corners area of New Mexico, near Farmington, where they live and flourish to this day.

In order to get back to their homes, the army escorted the 12,000 Navajo back to their homes  and, “the Long March” is one of the many things the Memorial commemorates. Imagine 12,000 Indians trudging back to their homes, the infantry in front, the foot soldiers in back and everybody else in between.

and, “the Long March” is one of the many things the Memorial commemorates. Imagine 12,000 Indians trudging back to their homes, the infantry in front, the foot soldiers in back and everybody else in between.

Fortunately, few people died on their trip back home and the census reveals that a couple hundred Navajo were actually added to their numbers. At that time Indians could be bought and sold as slaves and many in Santa Fe and Albuquerque escaped from their owners when the weary marchers were making their way through town.

They say that when many of the Indians reached the pass overlooking Albuquerque and saw Mount Taylor in the distance (a sacred peak in Navajo country), they broke down and cried. All this was explained to our tour group in exacting detail by Fort Sumner State Monument manager Scott Smith, a dynamic story teller and historian.

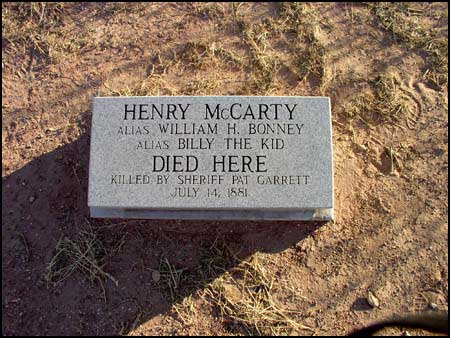

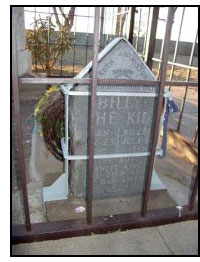

As the sun started to set in the horizon, we finished off the day by visiting Billy the Kid’s Gravesite, located a few hundred yards from Fort Sumner. A chill went down my spine as I stared at Billy’s gravestone. Oddly, the gravestone has been stolen a couple times in the past hundred years and luckily it has also been returned to its home.

As the sun started to set in the horizon, we finished off the day by visiting Billy the Kid’s Gravesite, located a few hundred yards from Fort Sumner. A chill went down my spine as I stared at Billy’s gravestone. Oddly, the gravestone has been stolen a couple times in the past hundred years and luckily it has also been returned to its home.

The gravestone is now firmly shackled into place and contained in what looks like a big jail cell. Placed near Billy’s grave is another stone that commemorates the place where his buddies were buried.

Thank you for visiting Chucksville.

|

|

|

|