Bird Watch

Bird Watch So, are you worried that our wildlife can’t make a comeback? Then visit the Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Reserve outside of Socorro, New Mexico and you might go home with a more optimistic outlook on life.

I recently attended a field trip to the 2005 Festival of the Cranes with a group from the University of New Mexico’s Continuing Education. A busload of retirees left Albuquerque in the early morning hours and arrived in Socorro about an hour and a half later.

We spent an hour visiting the Garcia Opera House where an arts and crafts show was taking place. The opera house was built in 1886 and, according to The Socorro Bullion was to be “the largest edifice of the kind in the Southwest.” It’s a curious old building, measuring 124 feet by 24 feet with curved walls that seem to defy gravity (and supposedly improve acoustics) as well as a “rake stage” whose rear is a foot higher than its front (for improved visibility).

We spent an hour visiting the Garcia Opera House where an arts and crafts show was taking place. The opera house was built in 1886 and, according to The Socorro Bullion was to be “the largest edifice of the kind in the Southwest.” It’s a curious old building, measuring 124 feet by 24 feet with curved walls that seem to defy gravity (and supposedly improve acoustics) as well as a “rake stage” whose rear is a foot higher than its front (for improved visibility).

Having “done” the Opera House, we headed out to the nearby Wildlife Reserve, along Highway 1. The Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge (henceforth “NWR”) consists of about 57,000 acres, situated along the Rio Grande in south-central New Mexico.

The NWR was established in 1939 an d its original purpose was to give wintering sandhill cranes a place to live during the winter. The cranes population had been devastated by the influx of people who moved to the area, as well as the building of dams and levees along the Rio Grande Valley.

d its original purpose was to give wintering sandhill cranes a place to live during the winter. The cranes population had been devastated by the influx of people who moved to the area, as well as the building of dams and levees along the Rio Grande Valley.

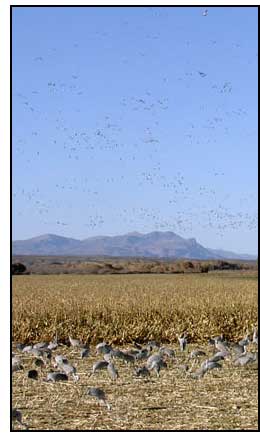

The establishment of the Bosque del Apache NWR has been successful beyond anybody’s expectations. In 1941 only 17 cranes were counted during the winter. Today, thanks to the manmade development of wetlands and food sources, the population peaks at about 15,000 cranes!

The NWR is a manmade habitat that mimics what nature can no longer do. Water is diverted along a sophisticated array of channels into fields that are planted with corn and alfalfa. Every few years the crops are rotated so the land can renew itself.

Fifteen thousand cranes (and at least that many snow geese) generate a lot of waste and the areas they visit must be allowed to to lay fallow for a few years  in order to prevent disease and massive die-offs of wildlife. The NWR has learned a great deal over the years (and made some mistakes) but now they seem to have the whole thing down to a fine science.

in order to prevent disease and massive die-offs of wildlife. The NWR has learned a great deal over the years (and made some mistakes) but now they seem to have the whole thing down to a fine science.

Local farmers, in a sharecropping arrangement, plant the corn in exchange for being allowed to harvest the alfalfa. The corn removes nitrogen from the soil and the alfalfa replaces some of the nutrients. 260 acres of corn are needed in order to feed the cranes and geese that visit the NWR during the winter. Corn is cut down to a height so the cranes can see over it and keep an eye on the ever-present coyotes.

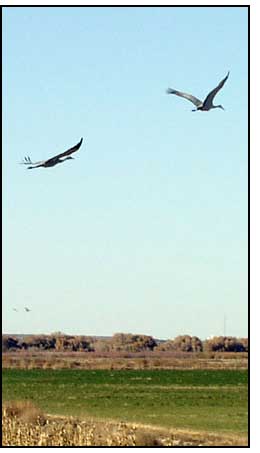

It’s a good thing to visit the NWR with somebody who knows the area because you never quite know where the birds are going to be at a given time. But once you find them, the experience can be overwhelming. Manmade “flight decks” and boardwalks can take you right into the thick of things, but since the birds are somewhat unpredictable, the action can happen right along Highway 1. So you’ve got to stay on your toes!

If you are an Alfred Hitchcock fan, the sight of all those cranes and geese may remind you of “The Birds.” It reminded me of an outdoor rock concert. Birds arrive slowly but surely and gradually fill up a field until it looks like it is covered in snow.

These birds react to human noises, like a car engine firing up but generally don’t fly away. Adults assume the “tall erect posture” while their family feeds, carefully studying the landscape for coyotes. If they see one, they will alert the others and take flight, much to the coyotes’ chagrin.

At night, having consumed their fill of corn, the cranes fly into the manmade marshes and roost for the evening. The “fly-in” to the marshes is a spectacular sight. The cranes then stand in the water all night on their spindly legs, no matter how cold it gets and are safe from predators.

As the population of this planet increases, the need for wildlife reserves is becoming more and more of a necessity. The need for such places may not be altogether easy to understand but it is becoming clear that when nature’s delicate balance is disrupted, man suffers. Gorillas, hippos and wolves are facing extinction in various places on our planet: We really need to start managing our wildlife better because our survival as a species depends on it.

Thank you for visiting Chucksville.

|

|

|

|