The Well's

Gone Dry

One score and twelve years ago, I visited the Washington D.C. area as a spry, young college student.

My girlfriend and I were taking a long road trip and we spent a few days with her folks in northern Virginia. Their colonial house was surrounded by acres of lush, green grass and one day I offered to cut it.

After mowing the lawn I jumped into a refreshing shower and at some point turned the water off so I could lather my body. When I turned it back on, the well pump had lost its prime and the water pressure had vanished. Only a drizzle remained and I was standing there covered in soap.

My cries of distress were met with suppressed laughter from outside the bathroom door. The pump eventually did start up again, but on that day I learned an important lesson about the reliability of old water wells.

The next morning, my girlfriend and I drove up to D.C. in her old blue Dodge Dart and we wandered through the National Portrait Gallery and the exquisite sculpture gardens of the Hirshhorn Museum where we saw sculptures by Rodin, Moore and Picasso. We also saw a play by Molière at the Kennedy Center but we did not spend much time at the monuments on the National Mall.

The next morning, my girlfriend and I drove up to D.C. in her old blue Dodge Dart and we wandered through the National Portrait Gallery and the exquisite sculpture gardens of the Hirshhorn Museum where we saw sculptures by Rodin, Moore and Picasso. We also saw a play by Molière at the Kennedy Center but we did not spend much time at the monuments on the National Mall.

My girlfriend was the most beautiful woman at my college and I was lucky to be her boy friend. But she wanted a commitment and all I wanted was to love her, so I eventually lost her to another guy who was willing to give her what I would not.

In November of 2009 I returned to Washington D.C. with my sister, determined to check out the monuments that I had missed 32 years before.

I scribbled down some notes from that trip and I’d like to share them now.

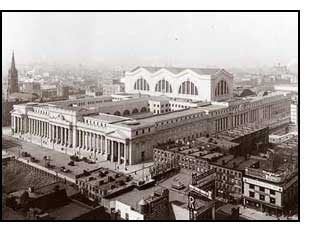

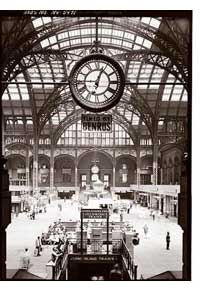

My sister and I are driving past Madison SquareGarden while America’s bullet train stops 60 feet below the street. Our cab drops us off near the giant Amtrak  marquee and we roll our bags into Penn Station, where a thousand trains come and go every day.

marquee and we roll our bags into Penn Station, where a thousand trains come and go every day.

Fifty years ago we would have entered a concourse built on the scale of St. Peter’s in Rome, but today we are crossing into New York’s hall of shame. Forever lost are the majestic Doric columns that graced a landmark lovingly built in 1910 and recklessly demolished in1963: a 300,000 square foot pink grani te temple, mourned to this day by train buffs and preservationists.

te temple, mourned to this day by train buffs and preservationists.

Just up the street from this renovated monstrosity is the old James A. Farley Building. It’s got Corinthian columns, terra cotta, and the whole nine yards. It was built in 1912 as a post office and bears the inscription: “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays  these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.”

these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.”

That building is every bit as pretty as the Old Pennsylvania Station and there’s talk on the street about turning it into a new train station for Amtrak. The sooner, the better, I say: Maybe if we all write the newspapers, our congressmen and the President, this idea will actually come to fruition.

North America’s busiest train station is quiet on this wintry Monday morning of January 2009, one week before the inauguration of President-elect Barack Obama. From the Acel a waiting room we watch a policeman lead a German shepherd across the polished floor.

a waiting room we watch a policeman lead a German shepherd across the polished floor.

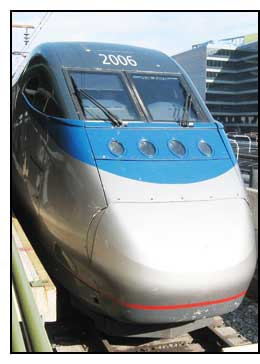

Prince, a redcap, leads us down an escalator to an underground platform where I feast my eyes on Acela, the flagship of Amtrak’s fleet. Its aerodynamic locomotive, originating from Boston and destined for Washington D.C., reminds me of a thoroughbred racehorse champing at the bit. Prince settles us into a train compartment and stores our bags overhead.

Most people don’t need Prince’s assistance. They are dapper commuters well-versed in the ways of high speed rail travel. But we are happy to tip Prince ten dollars for his trouble because everything seems so unfamiliar and strange.

Shelly and I sit in business class, next to a window, facing the direction of travel as this elegant train prepares for departure. Th ere are two seats on each side of the aisle and we can sit wherever we please. I’m wearing my Cumbres and Toltec engineer’s cap and my sister is dressed to the nines, toting her ubiquitous extra-large cup of coffee.

ere are two seats on each side of the aisle and we can sit wherever we please. I’m wearing my Cumbres and Toltec engineer’s cap and my sister is dressed to the nines, toting her ubiquitous extra-large cup of coffee.

At 51 years old there really aren’t many things that can get me excited, but the prospect of riding the rails at 130 miles per hour makes me giddy. What’s more, Shelly and I didn’t have to pay $150 each for our one-way tickets to Washington D.C. because I got them for free with my credit card points.

The Acela is a single level train, powered by powerful overhead electric catenaries, unlike most trains that run on diesel fuel.

The seats are ergonomic and recline, with retrac table trays and adjustable foot rests. The carpet and upholstery are stylishly designed and can easily survive the worst punishment. There is even a quiet car attached to the train where cell phone conversation and loud talking are not permitted. The windows are crystal clear and everything seems to work.

table trays and adjustable foot rests. The carpet and upholstery are stylishly designed and can easily survive the worst punishment. There is even a quiet car attached to the train where cell phone conversation and loud talking are not permitted. The windows are crystal clear and everything seems to work.

Overhead storage (similar to those found on an airplane, except larger and easier to stuff) is plentiful as are 120 volt outlets. Reading lights are conveniently located above every seat.

The walls of the train are so well insulated that I can barely hear a thing as Acela pulls out of the station. The train’s suspension system is solid but the ride can still be bumpy at times depending on the quality of the roadbed.

I leave my seat and examine every nook  and cranny of the train, snapping pictures along the way.

and cranny of the train, snapping pictures along the way.

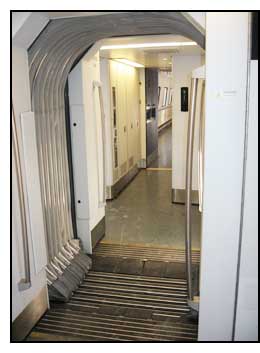

I am impressed with the way the cars are pieced together at the vestibules. Glass windows automatically open and close when I approach them.

The bathrooms are immaculate because the considerate passengers actually clean up after themselves. The faucet delivers a generous flow of water and shuts itself off after a reasonable space of time. The drain even has a rubber stopper handy for people who want to wash up.

The conductor tells me that the trains are running on concrete ties, but that many of them are being replaced due to substandard manufacture. The train reaches speeds up to 135 mph on this leg of the journey but can reach up to 150 mph between Boston and New York. Ordinary Amtrak trains top out at 90 mph.

but can reach up to 150 mph between Boston and New York. Ordinary Amtrak trains top out at 90 mph.

The most impressive thing is the way Acela takes a turn; you can feel the train tilt up 4.2° when it approaches a bend at speeds over and above 60 mph. The train’s tilting helps to counteract centripetal forces so that standing passengers will not lose their balance, seated passengers will not be squashed against their armrests, and objects will not slide all over the place.

I peer into the very front of the train and see something that looks like a bunch of torpedo shaped tubes. Then I feel somebody tap me firmly on the back. “No pictures, sir,” the conductor says. I return to my seat and spend the rest of the journey chatting with my sister.

Our trip terminates at Union Station in Washington D.C., a classically inspired marble, gold leaf and white granite structure designed by Daniel Burnham, who designed New York’s Flatiron Building and oversaw the construction of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Shelly and I are staying at the Holiday Inn near DuPont Circle, and once we settle in, we  head out to explore the town. The streets are clear of ice and snow and the subway system is a fast and easy way to get around town. The temperature hovers around 35 degrees under overcast skies.

head out to explore the town. The streets are clear of ice and snow and the subway system is a fast and easy way to get around town. The temperature hovers around 35 degrees under overcast skies.

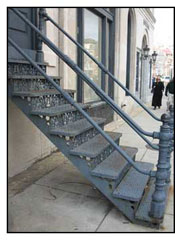

We pass an old rusting freestanding cast iron stairway that leads up to somebody’s front door. Then we walk by The Washington Post, home of the legendary team of Woodward and Bernstein, of Watergate fame. A  brightly painted linotype machine graces its entryway.

brightly painted linotype machine graces its entryway.

Then it’s off to the Capitol building and its new visitor center. Security is tight so we have to follow the usual protocol: We remove our wallets, belt and anything metal and place them in a gray plastic tray to be x-rayed. My sister is not allowed to bring in a fancy bottle of perfume, but a guard slips it into a rubber glove and tucks it neatly in the side of a garbage bin so that she can retrieve it on her way out.

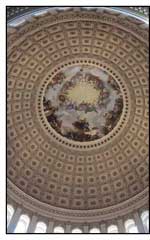

We enter the Rotunda and Statue Gallery, escorted by a docent who knows his art history. He goes to great lengths to explain all about the sculptures, paintings and architecture that surround us. He tells us engaging stories and is excited by our questions. He goes way beyond his allotted 20 minutes to teach us about the history of the Capitol.

We hike to the Washington Monument and take the elevator all the way to the top of the  555.5-foot marble obelisk, giving us a clear view of 40 miles in all directions. Then we walk to the rambling World War II memorial, with all its pillars, arches, plaza, fountain and engraved bas reliefs. It is so enormous and sprawling that I have difficulty taking it all in on ground level.

555.5-foot marble obelisk, giving us a clear view of 40 miles in all directions. Then we walk to the rambling World War II memorial, with all its pillars, arches, plaza, fountain and engraved bas reliefs. It is so enormous and sprawling that I have difficulty taking it all in on ground level.

The two highly reflective black granite walls that make up the nearby Vietnam Memorial are simplicity itself and much easier to comprehend, however. The Park Service had removed all the flowers, notes, beer cans and mementos that usually line the base of the  wall and has sent them to the Museum and Archaeological Regional Storage Facility for safekeeping. The memorial seems so naked without them.

wall and has sent them to the Museum and Archaeological Regional Storage Facility for safekeeping. The memorial seems so naked without them.

The names of 58,000 soldiers are engraved on the sculpture in the Optima typeface: A half inch in height and .015 inches in depth and are listed in order of the war’s chronology: A few names at the beginning of the giant V-shaped memorial, lots of names at its apex, trickling down to a few names at the end when the “conflict” ended.

a few names at the end when the “conflict” ended.

A trip to the Vietnam Memorial is a pilgrimage which begins at home and ends on the National Mall where one can locate a soldier’s name by leafing through the laminated pages of conveniently located index books. Having found the name of a loved one, a visitor can make a pencil and paper rubbing of the soldier’s name, pray, or leave an item of sentimental value.

Located nearby the Vietnam Memorial are two more realistic bronze sculptures that memorialize the  sacrifice and contributions of men and women to that war.

sacrifice and contributions of men and women to that war.

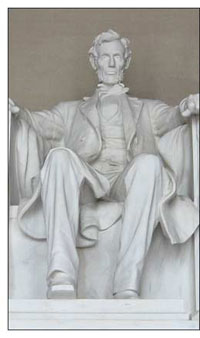

Next we visit the Lincoln Memorial. Workers are assembling a sound stage for the Inaugural’s entertainment but we were able to snake through the scaffolding and stand in awe before honest Abe.

Then we walk to the Korean Veterans War Memorial. It consists of 19 stainless steel soldiers in a field of wild juniper bushes. “Creepy” best describes this powerful assemblage of solitary warriors. I’ve seen plenty of sculptures cast in bronze but never in stainles s steel and this dull, grey medium sent a spooky chill up my spine.

s steel and this dull, grey medium sent a spooky chill up my spine.

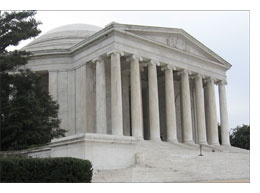

Finally, we walk around the tidal basin, with its cherry trees and see our last monument, the Jefferson Memorial, a domed colonnade that shelters a bronze sculpture of our third president holding a rolled parchment. Excerpts from his writings are inscribed on the walls.

All the above is a healthy hike, probably in excess of a few miles, but to my high-altitude blood it seems much less. We proceed to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum and check out the Spirit of St. Louis, the Apollo 11 space craft and all manner of crazy flying machines. I also get to touch a moon rock that connects me more with the millions of other people that have touched it than with our  nearest celestial neighbor.

nearest celestial neighbor.

We conclude our day by stepping into the Archives building and viewing the Constitution, Bill of Rights, Declaration of Independence and the Magna Carta. It is guarded by a multitude of policemen in a vault known as the Rotunda. It appears to be the most safely guarded place on earth, which is a real testament to the power of the written word.

At this point we are exhausted and make our way back to the hotel after enjoying a delicious Italian dinner, complete with old time music, wood oven-baked calzone and roasted vegetables.

* * *

We are heading back to NYC on a bumpy regional transport that does not tilt on turns. I cannot afford a return trip on the Acela, even with the few Guest Reward Points I had remaining in my account.

We are heading back to NYC on a bumpy regional transport that does not tilt on turns. I cannot afford a return trip on the Acela, even with the few Guest Reward Points I had remaining in my account.

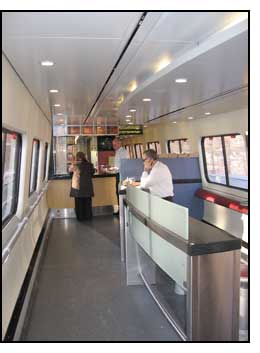

We’re cruising along at 110 mph, which is certainly fast enough for any mortal human being. The route appears to be the same as the one we followed to get to D.C., although we are making an extra stop or two. The vestibules are freezing cold and the train cars are utilitarian and fu nctional. But the café car is actually much more user-friendly than that found on the Acela. It has broad tables that invite you to settle in and stay a while. But overall, I think the Acela has spoiled me for life.

nctional. But the café car is actually much more user-friendly than that found on the Acela. It has broad tables that invite you to settle in and stay a while. But overall, I think the Acela has spoiled me for life.

I walk to a restroom.

The bathroom is spacious and clean, but you’ll never find the water flow anything like it does on the Acela.

I run the water and splash my face. I work the soap into a lather and apply it to my face an d neck, and my thoughts go back to Vienna, Virginia, 32 years earlier.

d neck, and my thoughts go back to Vienna, Virginia, 32 years earlier.

I think back to my first serious girlfriend.

One day my girlfriend’s father takes me aside for a heart-to-heart talk.

“What are your intentions, young man?” he asks me.

I hem. I haw. I don’t know what to say, so I don’t say much of anything because I am frozen with terror.

I didn’t think that fathers actually asked that question, but they do. They most certainly do .

.

I snap out of it and gaze at the mirror. It’s 2010 again and I’m riding on an aging regional transport, heading to New York Penn Station. I’m old now. My knee hurts and things don’t work as well as they used to.

I look at the mirror. My face is covered with frothy lather and I grope for the water spigot. The kind you press and you get maybe five seconds of spray. Meanwhile, the heavily perfumed Amtrak liquid soap is burning my eyes and no matter how hard I push, the water refuses to come out of the asinine spigot.

And no water will ever come out of that spigot fo r the duration of this trip because the train’s water tank has run completely dry.

r the duration of this trip because the train’s water tank has run completely dry.

Thank you for visiting Chucksville.

|

|